Some may or may not know that I am working on a book manuscript about Civil War Era New York City in which Theodore Roosevelt Sr., Frederick Law Olmsted, Louisa Lee Schuyler and a few others are the leading figures. Today is the 160th anniversary of one of the monumental moments in the American Civil War: it was on April 29, 1861 that approximately 3000 people turned out at the Cooper Institute to found the Women’s Central Association of Relief. Louisa Lee Schuyler was selected to run the day-to-day operations of the Women’s Central and did so with great efficiency during her tenure during the war.

Changing the subject a bit: I have noted over the past several weeks the anniversary dates of many Civil War moments, not least Sumter, Appomattox, and the Lincoln assassination. It’s difficult to imagine that the sesquicentennial began ten years ago this month. So much has happened over the past decade in terms of scholarship and current events that have changed our perceptions and memory of the war. It seems the war’s consequences and legacy are the main issues in the current narrative. This will continue as we recognize the anniversaries of events related to Reconstruction in the coming years, not to mention that 2022 will be the 200th anniversary of Ulysses S. Grant’s birth.

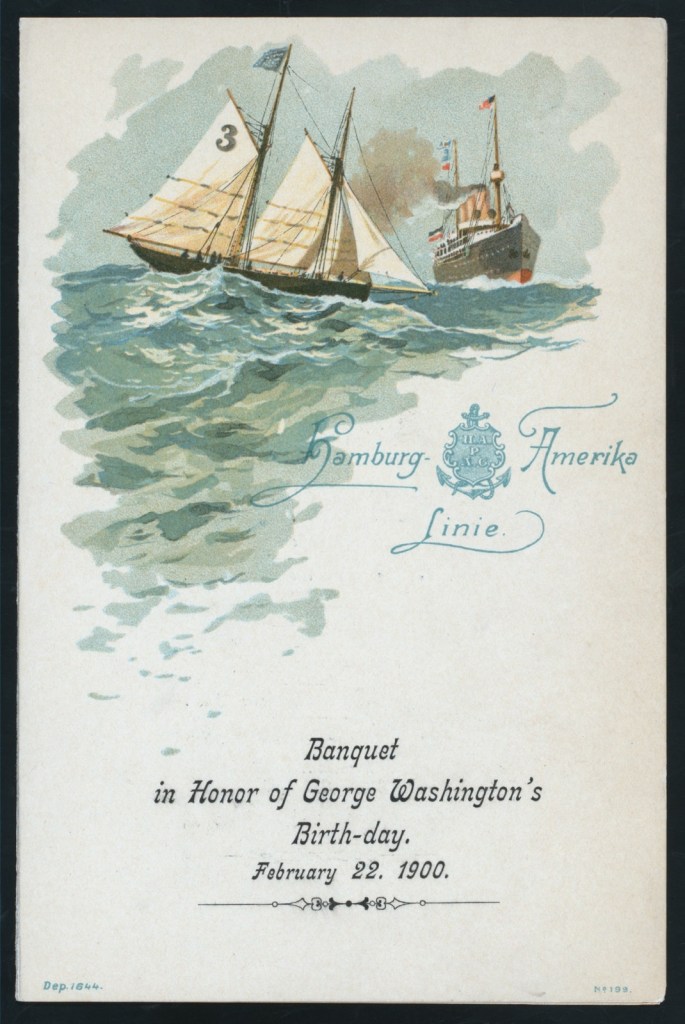

(image/Library of Congress)