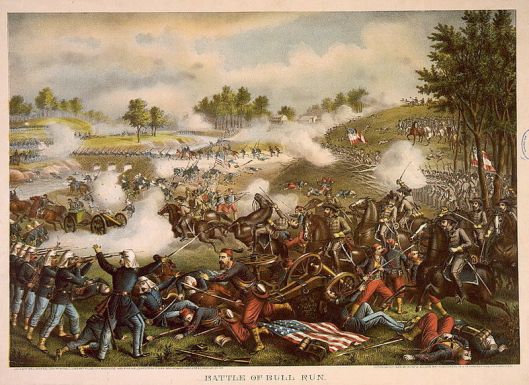

(Kurz & Allison; Library of Congress)

(Kurz & Allison; Library of Congress)

I am writing this from Washington, DC. Today marks the 150th anniversary of the First Battle of Bull Run, which took place only about thirty miles down the road. It was not until I began visiting DC regularly a few years ago that I realized just how close to the capital the Civil War occurred. Fifty years ago today New York State made some history of its own when it donated one hundred and twenty six acres of Virginia countryside to the federal government.

The monument to the Fourteenth Brooklyn was rededicated on July 21, 1961. Thankfully it today lies within park boundaries. (photo by William Fleitz, NPS)

The monument to the Fourteenth Brooklyn was rededicated on July 21, 1961. Thankfully it today lies within park boundaries. (photo by William Fleitz, NPS)

In 1905 and 1906 the New State legislature authorized the purchase of six acres of land for the construction of monuments for the 14th Brooklyn (later renamed the 84th New York), the 5th New York (Duryee’s Zouaves), and the 10th New York (National Zouaves). Each regiment was granted $1,500, which was the standard rate for such projects at the time. (The monuments for the latter two regiments were in recognition of those units’ actions during Second Bull Run.) The three monuments were dedicated together on October 20, 1906, with scores of veterans taking the train from New York City and elsewhere in a pounding rain.

Fast forward to the early 1950s, when New York State officials prepared to give the six acres to the Manassas National Battlefield Park. The deal became complicated, however, when the legislative Committee to Study Historical Sites realized that encroaching development threatened to cut the three monuments off from the rest of the battlefield. Chairman L. Judson Morhouse advised the state to buy an additional one hundred and twenty acres to ensure that the Empire State’s units would fall within the parkland. The state agreed and purchased the acreage in 1952. Later in the decade the New York State Civil War Centennial Commission, Bruce Catton Chairman, proposed to transfer the land to the Park Service during the 100th anniversary of First Manassas in 1961. Not surprisingly, the NPS was amenable to this and so fifty years today Brigadier General Charles G. Stevenson, Adjutant General of New York, handed over the deed to Manassas superintendent Francis F. Wilshin.

German-born Corporal Ferdinand Zellinsky of the 14th now rests in Brooklyn’s Green-Wood Cemetery.

German-born Corporal Ferdinand Zellinsky of the 14th now rests in Brooklyn’s Green-Wood Cemetery.