Hey everybody, as I mentioned the other day I spent Memorial Day weekend in our nation’s capital. Although my mother was born in Washington DC and lived there for several years as a young girl, I myself had never visited the city until just a few years ago. My favorite thing to do is visit the Smithsonian. The Hayfoot and I have had this on the heavy rotation since I returned last Sunday. One thing was surprised to learn when I visited for the first time a few years ago was that the Smithsonian Institution is not one site, but a system of museums and research institutions dedicated to preserving and disseminating our nation’s scientific, historical, and cultural heritage. Visiting Washington over Memorial Day weekend has whetted my appetite to learn more about the Smithsonian and its history. Earlier today I inter-library loaned some titles on the history of Mr. Smithson’s museum.

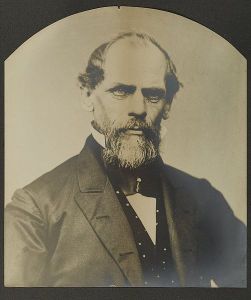

Ambrotype of Abraham Lincoln by William Judkins Thomson (1858); Smithsonian Institution’s National Portrait Gallery, Washington DC

Ambrotype of Abraham Lincoln by William Judkins Thomson (1858); Smithsonian Institution’s National Portrait Gallery, Washington DC

The Smithsonian also has a blog presence and is posting frequently about the Civil War, particularly on how the war affected the organization for good and ill. The museum was founded in 1846, just fifteen years prior to the start of the conflict, and as you can imagine was vulnerable on a number of different levels. According to a recent post:

As the war erupted in April 1861, the Board of Regents experienced a major upheaval, with more members leaving the Board over the course of the year. Several were expelled for their loyalty to the Confederacy, including Lucius Jeremiah Gartrell, a US Representative from Georgia, and James Murray Mason, a US Senator from Virginia. In June, the board lost another strong supporter when Senator Stephen A. Douglas of Illinois died. Douglas had been appointed to the board in 1854 and had been an advocate for the Institution in the Congress...

…As the war wore on, yet another member was expelled for “giving aid and comfort to the enemies of the Government.” Other strong supporters were also lost, including Jefferson Davis, president of the Confederacy, who had been a Smithsonian regent from 1847 to 1851, and was a close friend of [Smithsonian] Secretary Henry.

I can’t wait to go back next month. Until then, here is the next best thing.