Four years ago, just prior to getting married, I moved from an apartment I had lived in for twelve years to another about five blocks away. Overall, the move wasn’t much: same grocery store, post office, dry cleaner, etc, etc. The big change (other than the marriage) was that I was no longer so close to Prospect Park. An extra twenty minutes each way may not seem like much, but it adds an almost-prohibitive amount of time to a potential weekend walk or evening stroll after work. Brooklyn’s Prospect Park was designed by Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux and, though not as well-maintained, is very much the equal of their earlier Central Park. (Central Park is better maintained because the rich folks who live along its perimeter give piles of private money for its maintenance.) For me it was a big loss, though one that came with an equally big win: I am now just five minutes away from the gates of Green-Wood Cemetery. Green-Wood is one of the original garden cemeteries and is currently celebrating its 175th anniversary. To mark the occasion the Museum of the City of New York is hosting an exhibit titled A Beautiful Way to Go: New York’s Green-Wood Cemetery. It opened yesterday and runs through October 13.

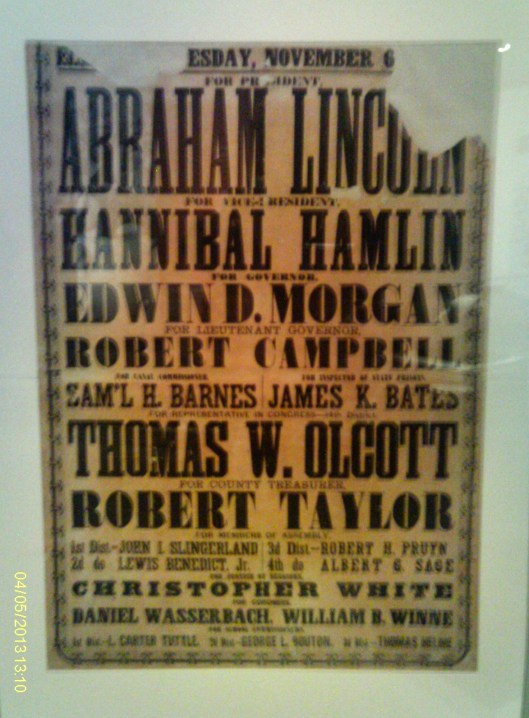

Garden cemeteries, sometimes called rural cemeteries, were a phenomenon of the nineteenth century, when American and European societies were industrializing rapidly and green space was becoming scarcer and scarcer for city dwellers. It may surprise you to know that in the late nineteenth century Green-Wood was the most-visited place in New York State after Niagara Falls. Graveyards are for the dead, final resting places for those who came before us and have now passed on; cemeteries are for the living, places to commune with nature and the past. One hundred and seventy-five years later Green-Wood is still serving this function. No matter how many times I have been there–and it is in the hundreds by now–I always see something new on each visit. It is not hard to do, whether it’s reading the many freshly-planted headstones of the 4,000 Civil War soldiers buried there, poking my head into the bars of a mausoleum to peek at the Tiffany windows, or seeing the sun hitting a familiar vista at a different angle during the change of seasons. I am looking forward to catching this show in the coming weeks, and will have more to say about it here on the blog after I do.