Last month I mentioned the ongoing fight within the Cherokee Nation whether to continue to recognize the Cherokee Freedmen as members of the tribe or to expel them for not being direct descendants tribe members. The Freedmen’s ancestors were once slaves belonging to members of the Cherokee Nation. My friend Susan Ingram is a former journalist who now works for a college in Oklahoma. She wrote this guest post:

As for now, the Cherokee Nation has ruled that the Freedmen are not tribal citizens, but a final decision from the U.S. courts is yet to come. This is a complicated issue of which there are no winners. The Cherokee Nation claims it is a matter of tribal sovereignty and self governance, not race. An independent nation existing and governing within a state, in this case Oklahoma, can be a difficult concept to grasp but it is a fact of daily life in this area. Oklahoma is home to 39 federally recognized Native American tribes (Oklahoma Indian Affairs Commission, http://www.ok.gov/oiac/Tribal_Nations/index.html) that coexist with many local cities, towns and communities.

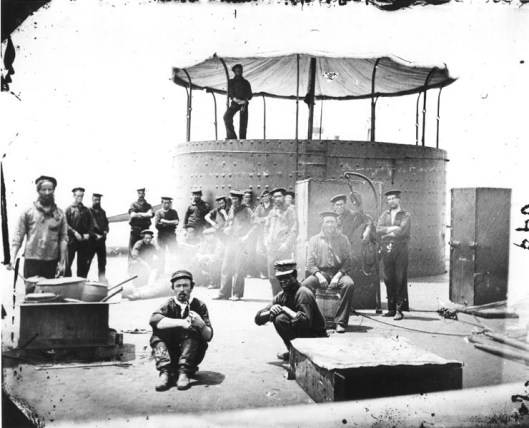

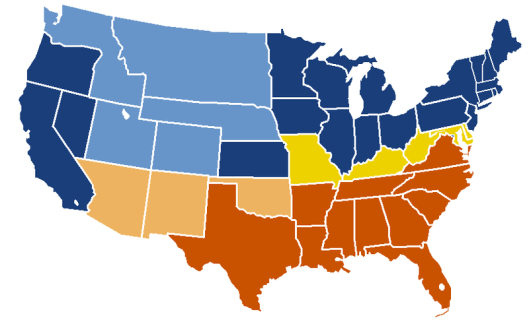

The controversy of the Cherokee Freedmen began after the Civil War when the Nation was ordered by the U.S. government to grant citizenship to its former slaves. The Civil War affected the Five Civilized Tribes the same as everyone else, dividing loyalties and families alike. Most tribal members joined the Confederacy, since they came from the Deep South and their way of life resembled that of others in the region. Many of them were also hostile to the federal government for its long history of breaking treaties made with the native tribes. Small bands of each of the Five Civilized Tribes did join the Union, however. With Indian removal being a part of recent history at the time of the Civil War, many tribes were still dealing with internal division and conflict. The war served only to further divide arguing factions amongst the tribes. Some of the skirmishes fought in Oklahoma were more about rival tribal factions than Union vs. Confederacy.

The issue of Freedmen citizenship has been building since then, and perhaps has now come to a head due to the recent prosperity of the Cherokee Nation. As the tribe’s population and wealth grows there is more at stake as to who benefits. Another possibility is that the Nation believes it finally has enough power and/or sovereignty to stand up and say they–and only they–will dictate who is a citizen and who is not.

Unfortunately the issue is not as precise as whose ancestor was on the Dawes Roll and whose was not. The Freedmen have lived with the Cherokee people for several generations and have married and had children with the Cherokees. The customs of the Cherokee people are the same traditions and customs of the Freedmen. Comparing the amount of African American blood to Cherokee blood that someone has doesn’t take into account the emotions, relationships, and values of that person. Nor does it account for the sense of family, identity and security that is now being ripped away from the Freedmen.

As a backdrop to this issue, the Cherokee Nation has gone through a heated battle this summer to elect a new principal chief. (http://www.tulsaworld.com/news/article.aspx?subjectid=520&articleid=20111020_520_0_hrimgs257246) At the heart of the election was the debate over including the votes of the Freedmen. The Freedmen won a legal victory when the courts determined that their vote for principal chief did count. It will be interesting to see how this story progresses in the future and whether or not the newly elected principal chief will make a difference in the fate of the Cherokee Freedmen.