Back in December I wrote about a portrait of Kaiser Wilhelm II in the collection of the Brooklyn Museum of Art that was saved from destruction during the anti-German hysteria of the First World War. Six months later in July and August 1918 the fate of another portrait of the Kaiser ended differently. This event took place in Oyster Bay, Long Island not far from Brooklyn.

Carl Henry Pollitz’s WW1 draft card. Mr. Pollitz remained in Oyster Bay after the incident and lived until 1966.

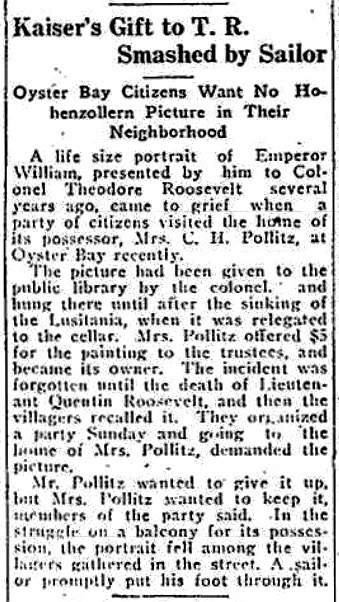

The destruction of the painting was covered in the German diaspora press. This article appeared in the Drumheller (Alberta) Mail on 19 September 1918.

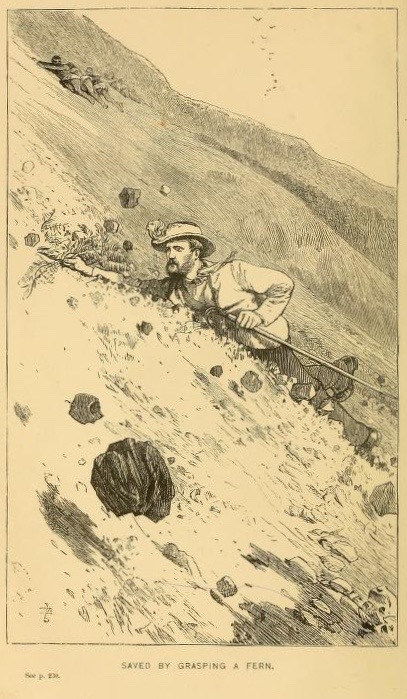

Apparently during Theodore Roosevelt’s presidency (the exact date is unclear), the German ruler gave the American president an autographed portrait of himself. Colonel Roosevelt eventually donated the painting to the Oyster Bay Public Library, which had the likeness on display until the sinking of the Lusitania in 1915. Old newspaper accounts vary slightly in the details, but the painting eventually came into the possession of one Carl Henry Pollitz and his wife Matilda. Mr. and Mrs. Pollitz were both naturalized Americans born in Germany. They owned the painting for three years until early on the morning of Sunday 28 July 1918 an angry mob gathered outside their home demanding the portrait. The couple had escaped to the roof with the painting and eventually handed it down. A sailor quickly put his foot through the Kaiser’s face. Similar events had taken place around the country but apparently the immediate cause of this one was the recent death of Quentin Roosevelt and the anger it caused.

Secret servicemen were dispatched to look into the matter and Mr. Pollitz, who said he knew some of the perpetrators, demanded action. That is where things stood for a few tense days until on Thursday 1 August an angry gathering of 1500 turned out in the public square. The painting was displayed on the tip of an old Revolutionary War musket bayonet for the angry crowd to see. They also sang the “Star Spangled Banner” and various anti-German songs. Eventually they doused the painting in gasoline and burned it.