Dr. David Waldstreicher opened discussing the Phillis Wheatley statue that stands on Beacon Street in Boston.

About 10-12 years ago I was having coffee with someone from work when we somehow got on the topic of Classic Studies. I mentioned that in today’s world the study of Classical Antiquity and Literature has been de-emphasized, to our detriment. I included myself in the category of those whose knowledge about these fields is woefully inadequate. That now-long-ago conversation came back to me last night when a friend and I went to the CUNY Graduate Center to hear historian David Waldstreicher discuss the progress of his current project, a biography of African-American poet Phillis Wheatley. Dr. Waldstreicher specifically mentioned our current generation’s lack of Classical Education. That so few people–again, myself included–have read the works of Virgil, Herodotus and others prevents contemporary readers from fully understanding the works of poets such a Ms. Wheatley, who incorporated themes from ancient texts into her own work.

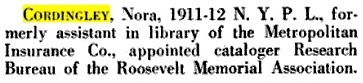

Dr. David Waldstreicher shows the audience an image of Wheatley’s writing with Thomas Jefferson’s hand-written notes on the bottom.

Dr. Waldstreicher said during his talk that for his biography of Wheatley he has had to educate himself in two areas about which he previously knew little, the Greek and Roman Classics & West African History. Wheatley herself had come from West Africa and later self-educated herself in the Classics. These experiences were pillars in her writing. It was impressive the way Professor Waldstreicher pulled all these threads together during his talk. In passing, he mentioned Jonathan Williams, Benjamin Franklin’s grand-nephew who was the first superintendent of West Point and who shortly after that worked on the forts at Governors Island. I spoke to Dr. Waldstreicher after his talk and mentioned these Williams’s connections. He seemed duly impressed.

Waldstreicher is a Distinguished Professor of History in the Graduate Center and an authority on slavery in the early years of the Republic. He did an extraordinary job explaining the fluidity of slavery in late eighteenth and early nineteenth century American society and how it differed from bondsmanship in the Caribbean and Brazil, and later in the United States. Apparently that his talk fell during National Poetry Month was a coincidence. If it was, it proved to be a fortunate one. The lecture gave the audience a great deal to think about, which was obvious in the number of questions asked during the Q&A period, which ran long. That’s the true sign that a speaker has engaged his audience well.