The Hayfoot was home for an all-too-brief visit this weekend. We intended to go to the New York Botanical Garden yesterday but decided to stay near the house instead. Waking early and getting all the way to the north Bronx just didn’t seem worth it. The weekend was for catching up, and catching our breath after the many changes of the last two months. It was good to hang out with those we care about. One thing we discussed yesterday was the logistics of our annual June trip to Gettysburg. It is going to be a little complicated, but things have a way of falling into place.

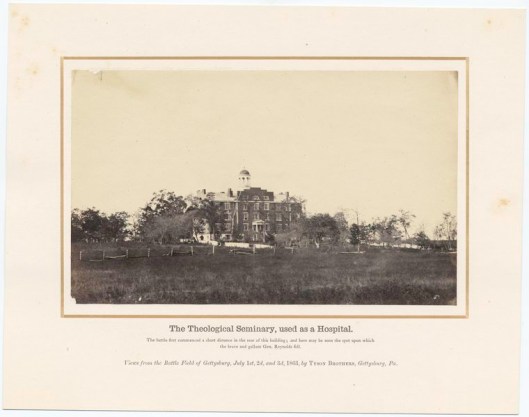

Today, as if on cue, I opened the mailbox and found an envelope from the Seminary Museum Museum. This new institution is located on the campus of Gettysburg’s Lutheran Theological Seminary and will open, appropriately enough, on July 1. I remember driving past the old building last year and seeing the renovations underway. They are doing a beautiful job. Unfortunately we will be missing the museum this year, as our visit falls before the battlefield anniversary. I would love to see it, but it is probably just as well; the museum will undoubtedly be a mad house in its opening weeks, which is without question wonderful but a pain for someone averse to crowds. This year in particular we are going to see some of the off-the-beaten-path sites, parts of Culp’s Hill, East Cavalry Field, and the like. (The evolution of why once heavily-visited parts of the battlefield now receive so little interest, and vice versa, is fascinating in and of itself.) The Gettysburg sesquicentennial seems an opportune time to see the more obscure locales.

Maybe if we are lucky we’ll talk friends into going to Gettysburg later in the year, when the crowds will be smaller. Whenever you are planning to go to Gettysburg, make certain to add the Seminary Ridge Museum to your must-see list.

(image by Tyson brothers, courtesy NYPL)