The Times understood the significance of the Monvel prints and advertised them heavily in the weeks prior to their release.

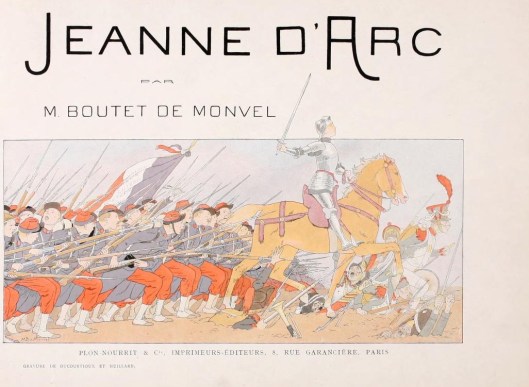

As you can see from the advertisement above the New York Times published a special Christmas supplement in early December 1914. What made it so special was the inclusion of several full color plates from artist Louis Boutet de Monvel’s Joan of Arc series. Monvel (1851-1913) had done numerous commissions about The Maid of Orléans over the years. Most famously these projects included a best selling children’s book and a ten panel masterwork in the church of the heroine’s hometown of Domrémy. Illness forced Monvel to abandon the latter project when it was twenty percent complete. The images published in the Times were reproductions of six much smaller panels Monvel had completed for Senator William A. Clark just before Monvel died. Clark hung them in his Fifth Avenue home.

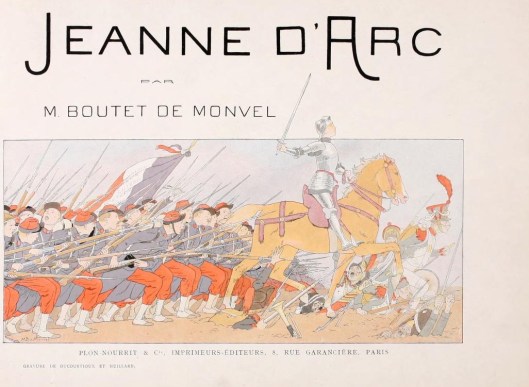

Monvel published the children’s book in 1895. The 15th century French soldiers depicted here look suspiciously like the zouave units of Monvel’s time. French soldiers first started wearing these uniforms in the mid nineteenth century and some continued through the first months of the Great War.

For the prints to be in the New York Times was a big deal. No one knew this more than the New York Times. The article accompanying the supplement describes the project as “The finest single issue of a newspaper ever seen in the world.” That is some serious hyperbole, but it has a ring of truth to it. The public snapped up 335,000 issues of the special edition, and would have bought at least 40,000 more if the printing presses could have handled the demand. Gushing letters of praise poured in from curators and directors at the National Academy of Design, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and what would eventually become the Brooklyn Museum of Art. People wrote in from as far away as Indiana.

The inserts were indeed beautiful, but there was more to the intense public demand than that. By December 1914 the Great War had settled into a stalemate on the Western Front. The war that everyone had thought would be over by Christmas now a muddy stalemate. Joan of Arc, that heroine of the Hundred Years War, was emerging as a potent symbol of Gallic resolve.

War as it is. This is one of the panels Monvel painted for Clark just a few years prior to the Great War. It is easy to see why readers in December 1914 would have been moved and inspired by the series.

It is unfortunate that the Times did not do something with these prints for the Great War Centennial. Indeed it is not even clear if the plates they commissioned a century ago–and paid a small fortune to reproduce–still exist. Thankfully the six panels from which they originated are still here. Senator Clark died in 1925 and bequeathed them to the Corcoran Gallery in Washington.

The Great War took all of France’s human resources. Among the poilus were Monvel’s son Roger and at least one descendent of Joan of Arc herself.